“Hope you are well.”

We are all guilty of typing those words. It’s the email equivalent of “Have a nice day,” though usually as a salutation. It means that in a few sentences someone is going to ask you for a favor. In customary parlance, it’s someone you haven’t heard from in quite some time. It’s also likely someone who doesn’t much care if you are well.

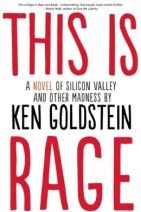

In the very early days of this blog, I wrote a piece of advice about networking. I thought about that a lot these past few weeks with the release of my novel. Launching a first book at mid-life is a somewhat absurd task. The odds of commercial success are so tiny, you almost can’t calculate them. When countless people in my network—from high school through college through each phase of my career—rallied to my support across the board, I was literally breathless. There is nothing I wouldn’t do for these people: job referral, job reference, resume review, preparation for a pitch, media training, media intervention, hospital visit, you name it! I am there for them in perpetuity, and they are here for me now.

In the very early days of this blog, I wrote a piece of advice about networking. I thought about that a lot these past few weeks with the release of my novel. Launching a first book at mid-life is a somewhat absurd task. The odds of commercial success are so tiny, you almost can’t calculate them. When countless people in my network—from high school through college through each phase of my career—rallied to my support across the board, I was literally breathless. There is nothing I wouldn’t do for these people: job referral, job reference, resume review, preparation for a pitch, media training, media intervention, hospital visit, you name it! I am there for them in perpetuity, and they are here for me now.

Don’t take this for granted. It does not happen by accident, nor does it happen as the norm. If you haven’t yet been crushed by that discovery, you will soon enough. Don’t be dismayed. Only you can fix the problem, and it’s a problem worth fixing. But it’s not a sticky patch on a leaky roof.

Networking is still so bizarrely misunderstood, it boggles my mind. It is not a system of stored and replaced favors. It is the building of bonding relationships where people want and choose to help each other. Pay It Forward is about as constructive a strategy for longevity as I’ve experienced. Relentless excellence and indefatigable commitment aren’t bad either.

If you want to have a robust network that might help you someday when you truly need the help, build it now; you’re already behind. If you think you can pull off a big-time favor swap real-time, you’re almost certainly deluding yourself. Build your network for the future by offering to do things for others, even if it’s an inconvenience. If you do it enough, some of that work will create powerful memories of connection, even more than appreciation. That’s a well filled with sweet water when you are someday thirsty.

At the very least, if you have nothing to offer someone, show a keen interest in what they do. A few weeks ago I gave a talk about my book at Stanford. I did it because a friend who loved the book asked me. My friend showed enthusiasm, her friend (the teacher) showed enthusiasm, I responded with enthusiasm. No tangible value was created, no business leads exchanged; it was all just goodwill. Yet that wasn’t what won in the networking. One of the students reached out to me after the class with a well-composed email discussing an enigma surrounding one of the characters in the book. The student asked me how that applied to a real-world work situation. It took me a while but I responded, which opened the door for the student to ask some more heartfelt questions. I liked the heartfelt part, that’s just me, but that student has now bridged access to what was once a total stranger’s network. To me, that’s good business practice. We’ll see how he works it over the next decade. I’ll bet he handles it well.

Here’s another example: A few years ago I was in a weekend workshop, not as instructor but participant. I saw promise in the material and was there for the learning. There were people at all levels of their careers and personal development; ages spanned four decades. One individual was quite young and struggling, fresh from college outside the United States, but passionate and curious about everyone’s life path. I asked her after the workshop to email me once or twice a year to let me know how her career was going. Strangely enough, she has. I’ve received about a half-dozen updates, not too many but enough that I remember her name and long-term goals. I’ve given her some advice, but nothing of real value yet. I’m guessing at some point I will. Maybe she’s banking on it, or maybe she’s just sincere. English is not her first language, but she has not as yet typed the words “Hope you are well.”

Staying in touch is not a onetime event. It takes work to be connected, give and take, sharing ideas and information, not just asking for something. If you don’t want to do the work, don’t bother extending the outreach. You would be shocked at how many people I’ve suggested stay in touch with me after an initial meeting and never do. They forget, or they don’t care, or they don’t see value in it, or they are disheartened by the lack of immediate gratification. I am grateful to them. It helps me manage my workload—one less rising star I might someday champion.

Watching new grads bang their heads against the job market is terribly frustrating, because they haven’t had the experience to know how they could approach it better, with fortitude and resilience. Watching later career professionals suffer the same resistance is even more frustrating, because by now they should have powerful networks of their own, but if they didn’t invest along the way in others, that network today is likely too thin. Remember that LinkedIn and Facebook are tools, but networks are between people. The glue that bonds networks is history, and history comes from doing things, often and selflessly, for and with each other. When it comes to bolstering a platform of human support for your unlikely and unexpected needs, you’ll need to make that brand deposit now for future withdrawal. No surprise, you have to Think Different. It’s not a quid pro quo, you don’t get a favor for giving a favor (not a good one, anyway), but if you authentically invest in goodwill, you’ll enjoy a deep reserve of goodwill. When it’s time to dip your ladle, you want it to be an underground lake.

Networking is not what you can do for me. Networking is what I can do for you. Before you ask.