Here’s something people often say in companies when you ask them what they accomplished last week, last month, or last year:

Here’s something people often say in companies when you ask them what they accomplished last week, last month, or last year:

“A lot of time is taken up by everyday stuff.”

Let’s talk about that. What is the everyday stuff? Is the work being produced commensurate with the expense?

A few years ago I wrote a post called Too Busy To Save Your Company. I refer to this post often when I am asked to look at a company and comment on why it is not as productive as it should be. It can be a consulting or investment meeting, but when I see lots of people running around or pounding on keyboards but an income statement in decline, I usually start by asking a few key people in the company to describe their days to me.

They often tell me that they spend a lot of time going to meetings and responding to email. When I remind them that meetings and email are not tasks, they are tools for accomplishing tasks, there is often an “Aha Moment.” That’s when I know we can make some progress.

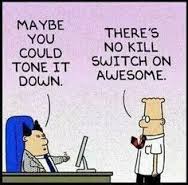

You are wasting time. It is inevitable. How do I know? Because I waste time. Everyone does. No one is 100% efficient. The question is one of scope. Do you own your priorities or do distractions own you? When you start there, you begin to take control of your destiny.

Time management is neither a touchy-feely topic nor a chokehold on creativity. It is how you allocate your most precious and perishable resource, the ways you choose to spend your hours. The portion of your time that is discretionary and how you choose to utilize it is the difference between having a shot at winning and losing for sure. Note that I say it is a choice, because even if you don’t make active decisions about how you spend your hours, the choice to squander time remains a choice.

Try this exercise for a week: Write down hour by hour what you do on the job. If you spend an hour on researching the cost of something, write that down. Log each of your phone calls and meetings chronologically. More importantly, note what you were talking about and if any key decisions were made. Be as detailed as you can. If you read an article on the internet write that down, including what you learned or didn’t learn. If you shopped for yourself, chuckled through laugh-inducing videos, or commented passionately on Facebook, account for these by collecting them into small blocks of time. Don’t worry about the confession, you can delete the audit later. Be brutally honest and exceptionally thorough. This is solely for you.

Now go back and look at your goals for the year. If you don’t have any goals, that’s a much bigger problem which you need to solve before this post will be relevant to your progress. I’m going to assume you have 4 – 6 overarching annual goals agreed upon with the people who pay you or your partners, stuff like “increase sales 25%” or “decrease customer complaints 10%” or “launch 2 new apps per quarter” or “hire 15 regional salespeople.” You get the idea, stuff that matters, the stuff that keeps you from falling into the trap of being too busy to save your company.

Color code each item on your time accounting to match one of your goals. Try green for sales or blue for product improvements, soothing colors of accomplishment. If a block of time doesn’t match up with a goal, use a different color for DOES NOT APPLY TO A GOAL. A good color for this is red because it should be a warning color.

If you see very little red and an even distribution of the other colors against your 4 – 6 goals, you’re doing fine and can stop reading here. Congratulations, you are in perfect harmony and have a well-balanced calendar. As long as your company is growing and generating a healthy profit, this post is not for you.

On the other hand, if what you see is a disproportionate allocation of color — say, 80% blue but you have 4 other goals with minimal color showing— you are out of whack. If what you see is a sea of red, either quickly finish this post and get back to work or find another good post about writing a resume.

Now on a clean calendar, I want you to block your time as you should be spending it. If cold calls are 25% of what you should be doing, block 10 hours per week; it can be 2 hours each business day or 5 hours twice per week, whatever you fancy. I know, you work way more than 40 hours, but for budgeting purposes use that as a baseline.

Now compare the calendars. Want to know why you are not making a bigger dent in your goals? That’s why.

Time management is a subject I address regularly with colleagues as a proactive tool. Each time I assemble a new team, I have this talk with the senior people about their own time management and how seriously they take it, manage it, and monitor it. Leadership by example, right? The people who take it seriously are usually much more successful than the ones who blow it off. At its core, it is active versus passive resource management. Time lost is unrecoverable.

Oh, one more thing: Please don’t forget to set aside time for brainstorming and dreaming. Sometimes we call that shooting the sh*t. If it’s about stuff you think doesn’t matter, it might be wasteful. If it leads one big idea in a year, it can transform your business. Leave time to shoot the sh*t productively. The 5% to 10% of your time you leave for dreaming is where real change starts to happen and companies begin to reinvent themselves. If every minute of your day is consumed with scheduled or forgettable tasks, big ideas are going undiscovered.

Don’t leave all your time to everyday stuff. Do stuff that matters. Then dream on.