I have mentioned now and again that I have been working on a novel for a few years. It’s time to share a few more details.

I have mentioned now and again that I have been working on a novel for a few years. It’s time to share a few more details.

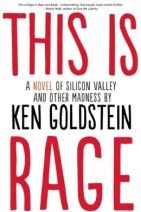

First of all the title: This Is Rage. You will discover why I called it that if you read the sample excerpt on my teaser site and other fine channels we will be utilizing in the coming months, like Amazon or Barnes and Noble, where you can currently place your pre-order that will be shipped when the book is officially released on October 8, 2013. Shameless, I know, but I am officially in the pull marketing business effective immediately.

There are two protagonists in the story, who are also both antagonists, at least to each other. They are each hero and villain in the broader context of economic turmoil, which they aspire to improve, but not surprisingly mess up on high-octane, mostly by accident. Kimo Balthazer is a disgraced radio talk show host, who seeks redemption in the obtuse netherworld of internet webcasting. Daniel Steyer is a venture capitalist at the top of his game, looking to go out huge with the deal of a lifetime, but market forces have other plans. That’s not the order in which you will meet them, and you’ll find out why. At the outset they don’t know each other exists. They don’t even know each other’s world exists. But they soon do. And they don’t like each other. At all.

I am going to do the right thing and not toss out any spoilers, but I can say that you will spend some time in Silicon Valley, some time in Los Angeles, and some time in Washington D.C. You will be introduced to the world of Investors, Bankers, and Operators, the three points of an ever-forming triangle that comes with its own hierarchy, rule set, chaos, and politics. You will also meet a curious politician with a tangential agenda, a conflicted movie studio boss, the co-founders of one of the most successful tech-start-ups ever, and a pair of would-be entrepreneurs turned criminals whose interpretation of thinking different is not quite what their families had in mind. You will be invited into board meetings and venture partner meetings. You will hear the voice of Kimo in your head. You will see what happens when ego and presumption run amok, and the notion of control spirals into hyper normalcy, where random boo-boos add up big time, and the consequences are strangely real and familiar.

My key influence for this book is Tom Wolfe, whose first novel Bonfire of the Vanities blew my mind in ways that still shake me to the core. I didn’t know what a bond trader was the first two years I was in college. Then I saw a bunch of guys my age lining up in blue suits to be interviewed to become one. They went to Wall Street and became extraordinarily wealthy selling paper promises to their clients. Then came the broad implosion of junk debt. Michael Lewis, whom I also tremendously admire, made his debut as an author writing about this phenomenon. I saw the impact on my friends, I saw the impact on New York, and I felt the impact on our economy. What I admire to this day about Wolfe’s work was how he wove storytelling through the observational narrative, migrating the educational lesson to character development, and burying the polemic in a moral tale for the ages. I was studying theater at the time, without notion of how I might fit into the business world, or even if I could make a living given what I valued.

A quarter century later we seem to have forgotten the fall of the junk bond kings. The miracle of Silicon Valley has replaced the lustre of Wall Street and the allure of Hollywood. I have played my whole career in this fantastic environment of innovation, the arranged marriage of technology and media brokered by the matchmaker financiers, and the output had been invigorating. We have created jobs, opportunities, and a good deal of wealth — but not for everyone. In the same way that Wolfe and his New Journalism looked beyond the restaurants and clubs and luxury high-rise suites, I have seen the scary trailing the good. Where there is big money there are big personalities, and where there is a win-lose battle fought daily, often those who lose are the secondary foils who play by the rules without insight into the eccentric ecosystem.

That is the story I wanted to tell. That’s why I wrote a business novel instead of a non-fiction set of adages. This was something I needed to do, part of the continuum of my journey. I started my career in storytelling, then helped bring storytelling into computer games, then found my way into profit and loss, and now I come full circle. I needed a way to bring these elements together, to find a synthesis of my passions, which include the theatrical, the financial, the philosophical, the hope of justice, and a touch of dark humor (hopefully more than a touch!).

In the coming months I will tell you more about the publishing journey, but I cannot conclude this project announcement without a sincere thank you to my brilliant editor, Lou Aronica, under whose independent imprint The Story Plant my book is being published. Lou is a Mensch in every sense of the word (Google it if that’s unfamiliar to you). He has been a steadfast believer in This is Rage since we met each other last year on Twitter. It’s not just the notes that he gives me, it’s the way he communicates his viewpoint that makes me want to rewrite a fourth time when he is only asking for the third. I think Lou, a bestselling author himself, is at the forefront of New Publishing in the same way Wolfe wanted New Journalism to embrace the opportunities of Creative Destruction as a positive force for change. Wherever this journey takes us, I am delighted to be paddling alongside a friend on this whitewater river of 21st century digital publishing — with a paperback to boot.

So that’s the introductory story of my novel. It’s my first, I hope not my last, and I welcome you to come along and share the journey with us. It’s for you, and it’s about you. I hope to entertain, and maybe share an idea or two as the whitewater rises.

This is Rage.