Here’s a phone call I sometimes receive, usually from someone senior in executive management or the investment team behind a once promising company:

Here’s a phone call I sometimes receive, usually from someone senior in executive management or the investment team behind a once promising company:

Inquirer: Hey, we need your help with something. We have a situation and we’re not sure what to do about it.

Me: Sounds intriguing. What is the situation?

Inquirer: Well, we’re having… I’m not sure what you would call it exactly, I guess a problem with morale.

Me: What would you like me to do?

Inquirer: We would like you to help us fix morale.

Me: Oh, that. I’m sorry, I can’t help you.

Inquirer: We haven’t spoken two minutes and you already know that?

Me: Yes, I’m quite sure. I certainly would like to take your money because I’m sure you are willing to pay a lot to do something about this, but I only take on projects where I can actually help someone.

Inquirer: How can you be so sure?

Me: You can’t fix morale.

Inquirer: What do you mean? Morale gets fixed all the time.

Me: Yes, exactly. Morale gets fixed because whatever is causing it to deteriorate gets fixed, but that is where you need to look, at the disease, not a symptom.

Inquirer: Are you saying we need to fix something else in our company so that maybe it can have an impact on morale?

Me: Yes, that is what I am saying. In fact, you probably need to fix your company.

Inquirer: So a contract to fix morale is not big enough for you? You want a bigger contract to fix our company? But our company is not broken.

Me: Then you probably don’t have a morale problem and don’t need any help.

Inquirer: You’re not doing yourself any favors turning this down. It’s a big project. We have a sizeable budget for it.

Me: It’s tempting, but why don’t you have another look at the situation and maybe we can talk again.

The call usually ends there and we don’t talk again. Every once in a while we do talk again and then I tend to get involved in long stretches of dialogue with team members up and down the line. We talk about a lot of things: leadership talent, product quality, business model. We talk about creativity and innovation, passion for excellence, dedication to the customer experience. One of the things we never talk about is trying to fix morale.

Let me say it again: You can’t fix morale.

Bad morale is a byproduct, most often of poor direction, sometimes of impossible goals so ridiculous no one ever feels appreciated, other times of uneven credit and compensation in times of success. There are successful companies with good and bad morale, and struggling companies with good and bad morale. Good morale is also a byproduct — you achieve it by focusing on the right things.

I view morale as a result of process and outcomes. Process involves day-to-day workplace routines that reinforce or strip away employee engagement. Outcomes involve the continuity or deadend at the culmination of a milestone, the reward or repudiation for the commitment of time, expertise, or passion. If your process is bad, morale will be bad. If your outcomes are bad, morale will be bad.

Suppose your company wildly missed earnings targets three quarters in a row. You’ve seen your second round of layoffs in less than two years. More than half of your VPs were fired and hired in the past ten months. The CEO, also rumored to be teetering, has said repeatedly everyone needs to “work smarter, not harder,” but no one is sure which product in the pipeline is going to carry the day. Employee morale as you would expect is rotten all around you. Your colleagues are irritable and nasty. Every week someone you like leaves the company for another gig.

Let’s look at some options for addressing this:

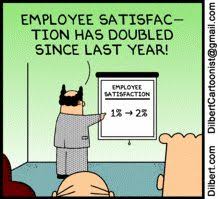

- The company hires a consultant to run a survey on employee satisfaction and weeks after you fill out your survey they find out what everyone knew before the survey: Morale stinks like a decaying carcass. The CEO announces Fridays will be half days, the company will be publishing a weekly newsletter celebrating its best employees, and all VPs and above will be taking classes in how to write better reviews and talk nicely to their teams. Everyone is told he or she is appreciated and reminded to work smarter, not harder.

- The company holds an executive offsite where all the VPs get to articulate everything that is wrong with the company. The VPs report back to their teams that the CEO agrees, there are not enough resources in the company to go around, the timelines for deliverable are insane, and the competition has an edge on the industry that is daunting. Starting today you will have realistic goals, more resources, flexible timelines, and as long as everyone is doing their best, then management will back off and be satisfied.

- The CEO pulls together a half-dozen of the best minds in the company to conduct an honest post-mortem of why the company’s strategy is failing. That team then strips away all the derivative efforts that are draining resources from the company’s true mission and recommits to a narrowed product strategy that capitalizes on the company’s identified competitive advantage. The CEO then directs the executive team to align the best talent in the company with key roles on the narrowed agenda and hire new talent where mediocrity is being tolerated, then communicates the new plan to the full company in verbal and written detail, not just in an inspiring kickoff speech but in regular progress updates that are candid and coherent.

You might think the answer is obvious, but sadly it is not — especially to less experienced management teams where too many influential individuals have achieved authority through battlefield promotions. Here we are talking the bedrock of directing process and refocusing outcomes. Good process takes a lifetime to learn. Steering through outcomes whether planned or unplanned requires a deft touch. There are no shortcuts. If you don’t have the energy or commitment to take apart process and outcomes one building block at a time, you have little shot at repairing morale.

I often ask people to share with me whether they have had a single good manager in their careers. You would be surprised how many say no. In fact these days it is the rare exception of people who actually rave about a boss from the past and talk about how they are putting that learning to work. The ones who are tend to have fewer morale problems on their hands. Too many leaders’ lives are filled with morale problems because they haven’t learned how to steer past them.

Now think about all those unicorns out there — you know, the 150 or so privately funded startup companies currently valued at $1B or more. Those should be some of the happiest places in the world for people to work, big idea places filled with promise and hope for future riches. Go take a random walk through those gardens on Glassdoor. You might be surprised at what you find. They have a lot of problems. When the majority of them are unable to achieve liquidity for their option holders, they will have even more. With that will come a wave of demoralization sweeping through employee workstations. How would you go about fixing that?

You can fix a product. You can’t fix a byproduct. Fix what’s wrong in your company, not the normal human emotional reaction to what’s wrong in your company.

You certainly can fix engagement. You fix engagement through authentic vision, brilliant product design, and a rallying cry around consistent execution. Fix engagement and morale fixes itself.

Align the finest talent you can identify with challenging projects that allow them to do the best work of their careers. Keep an eye on process. Celebrate outcomes and share the wealth. Be generous with people who are meaningfully contributing to company success. Morale will be swell and you’ll have bragging rights to let everyone around you know what a great environment you’ve created for the next wave of outcomes.

____________

Image: Dilbert.com ©Scott Adams