For many of us the new year begins with the best of intentions. It’s not so much that we delude ourselves in committing to resolutions we will never pursue as it is the open calendar before us filled with possibility and promise. What can we do with all of those days between now and the end of the year? The choices are as endless as the opportunities.

For many of us the new year begins with the best of intentions. It’s not so much that we delude ourselves in committing to resolutions we will never pursue as it is the open calendar before us filled with possibility and promise. What can we do with all of those days between now and the end of the year? The choices are as endless as the opportunities.

Almost immediately we start falling behind in our daily tasks. Days into the new year we are already playing catch up. Why can’t we get ahead of our task lists and beat the daily grind into submission? Why can’t we focus on projects and prospects that matter? Why do we spend endless hours on stuff but still waste so much time?

Maybe it’s just too easy to kick the can.

Difficult challenges don’t sort out themselves. They have to be wrangled and wrestled. That’s the kind of intellectual and emotional commitment that takes the force of will to muster. If you want to achieve meaningful progress, you have to get ahead of your calendar, not let it consume you.

Want that glorious promotion at work? It’s not going to find you.

Want to make a significant dent in your competition? They aren’t going on vacation to give you breathing room to pounce.

Want to learn a new skill, a new language, accelerate your ability in an artistic discipline, or finally figure out why your department is going sideways instead of upward? Those are all really difficult things to do that won’t take place between Facebook posts or tweets.

If you want to stop drowning in your dizziness, learn to think proactively. Set your sights on a potential outcome and work your way back to the present. Envision a roadmap and establish a set of checkpoints that will lead you to a better outcome. Own the outcome by owning the process.

Most important, you need to do it now. Not in a month. Not in a week. Not tomorrow. Not in an hour. Now means now.

Procrastination will cost you your dreams. If you have dreams, you need to act on them. Even if you don’t have dreams, and you should, if you have stuff to do that will make you more successful and personally fulfilled, you need to do it immediately.

Not after breakfast. Not after lunch. Not at the day’s end when you are exhausted, pissed off, and want to climb under a blanket. Do it now.

I don’t care if you’re busy. We’re all busy. If you are putting off the stuff that matters for busywork, knock it off. Do the hard stuff first. Busywork is a punt. People do busywork to look busy, often at the expense of making a difference.

What does it mean to be proactive? It means not waiting to be reactive.

Reactive is a deflating death march of punch lists.

Proactive is an uplifting rallying cry of planning.

Reactive is missing a sales forecast and formulating a remedy to catch up on lost business.

Proactive is outpacing a sales forecast by building customer loyalty through surprising and delighting.

Reactive is compiling a list of customer complaints bludgeoning customer service.

Proactive is regular ride-along listening sessions in customer service to turn suggestions and trends into repeatable wins.

Reactive is lowering prices to steal market share with thin margin transactions from customers who will easily abandon you to save pennies.

Proactive is designing a brand that is equal parts price, service, and quality so that small fluctuations in price become ignorable noise to your best customers.

How do you stop being helplessly reactive? You have to commit to the habits of being a self-starter. You’ll know you’re a self-starter when your boss asks a question in a meeting and everyone looks at you to serve up a suggestion fearlessly.

Ready to be a self-starter?

You need to move faster. If you thought something was going to take a week, do it in a day. Force yourself to accelerate.

You need to act with higher quality. If you thought good enough was going to please a customer, you’re wrong. Exceed their expectations.

You need to utilize fewer resources, not more. Use every tool that is available to you and don’t worry about what you don’t have.

The formula for reinvention is better, faster, cheaper. Not one, not two, not two and a half, all three.

What does being proactive mean?

Proactive means to take on a task before someone asks you to do it. It means to finish the task with excellence before someone even knows you started it.

Proactive means knocking the stuff off your to-do list that will have an impact, not the maintenance stuff that no one will notice.

Proactive means knowing that email is a tool, not a task. Unless you work in customer service, no senior executive is going to promote you because you answered all your email.

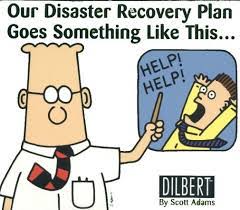

Proactive means plan for a crisis by avoiding it. If you’re dealing with a surprise crisis, you’re already reactive. Anticipate the crisis. Write down your response to the crisis before it happens. Scenario plan. Have notebooks filled with scenario plans.

Proactive means investing in quality assurance testing at five cents on the dollar instead of a product recall at 200 cents on the dollar.

There aren’t that many commonalities in the success stories you may admire, but one that holds true is urgency. Setting priorities, making time for abstract planning before reporting memos consume you, carving out blocks of time to schedule the milestones of your challenge — that’s how big things in your life will happen.

No outsider will hold you to the promises you make to yourself. You have to decide you want to be proactive. Then you have to remain consistently proactive.

Someone has to make change happen. Why not you? Your future outcome is at this moment in the making. Think about how you could be feeling this time next year if only you can get ahead of your day.

Being proactive is more than a choice. Being proactive is finding the freedom to make this year a year like no other.

____________

Image: Dilbert.com ©Scott Adams