You might have noticed I’ve published fewer blog posts this year. The political climate has made it hard to write about things that seem trivial in comparison. I’ve found it difficult to comment on news of the day without adding divisiveness to the national dialogue, yet unsettling to try to ignore it with distanced topics. I suspect I’ll resume my regular cadence at some point. I’m not sure when, but I will remain at the keyboard infrequently as my DNA requires.

You might also have noticed that the Los Angeles Dodgers just won the World Series for the second year in a row. That is another infrequent happening, and while perhaps not life-changing, joyously worth a few comments from a devoted fan.

The entire MLB postseason this year was filled with unpredictability. The World Series was a fitting final act to that rollercoaster, with an 18-inning marathon Game 3 and a fought-to-the-finish Game 7 that went down to the last swing of the bat. I won’t recap the play-by-play, others have done that with endless detail, but I will say it was a game that turned on both the performances of superstars and journeymen.

That’s one of the things we love about baseball. Any team can beat any other team on any given day, no matter how good or bad. Chance is always at play. A ball can literally get stuck in a wall crevice and change the outcome of a game (it happened in Game 6). A series MVP like pitcher Yoshinobu Yamamoto can demonstrate consistent excellence on the mound in the clear sight of Sandy Koufax, or a little-known infielder with heart like Miguel Rojas can come off the bench and tie a game that seems all but lost.

Impact can happen at any moment from any player. The game can seldom be predicted.

What does this innocent children’s game played by highly trained adults teach us? We learn from the applied metaphor of baseball that you always play hard to the end. Resilience is your heartbeat. It pays to be indefatigable. You never give up. Never.

Baseball is so many things in the mirror of life. It is the ultimate combination of athleticism and strategy, training and statistics, physical readiness and endless number crunching. It is a game of mistakes — the only sport that counts them on the scoreboard. It is a game of overcoming failure, where a player who gets a hit 2 out of 10 times at bat usually gets dumped, and a player who hits 3 out of 10 often will be paid millions of dollars — crazy many millions of dollars. Unless you are a pro, you’ll never see a 100 mph fastball whip by inches from your body. In fact, the pros can’t see it either, but sometimes they time their swing right, make contact, and put it in the outfield stands.

I had hoped to see the Dodgers win the World Series at home for the first time since 1963. Not only didn’t that happen, but we lost both games I attended with my brother, who was quite the ballplayer in high school and college. So was my dad, who couldn’t attend this year, but texted me at every key moment with his coaching suggestions. I never had the talent, but curiously, I was pretty good with the numbers.

When we lost both those games, I thought of a marketing idea for the front office: how about they give us a 5% rebate for every run we lose by? So if we lose 6 to 1, we get 25% of our ticket price refunded. This would just be for the wildly overpriced World Series tickets. I’ll be sharing that concept free of charge on my annual season ticket feedback form. I don’t expect a response.

The two games we lost at home were more than offset by the final two games we won on the road. The drama of those two games would make for an Academy Award winning movie no matter who won. Note to Kevin Costner, Redford is unavailable — do you have one more baseball epic in you? And who would you like to play?

Hats off to the Toronto Blue Jays, who have waited since 1993 to get back to this big stage. Their ball club oozes talent, from the future Hall of Famer Vladimir Guerrero Jr to the wild ascent of pitcher Trey Yesavage from Single A minor league ball to triumph in the World Series seven months later.

The Dodgers magical starting lineup — Ohtani, Betts, Freeman, Smith, Muncy, Edman, Teoscar Hernandez, Kike Hernandez, Pages — will live in our imagination with most returning for another season. We also witnessed the impossible elegance of an unknown reliever in Game 3 named Will Klein, and in that same game the single inning bridge of the departing great Clayton Kershaw. Manager Dave Roberts made a number of gutsy, counterintuitive moves throughout the series that could have gone either way, but at last the risks played in his favor.

Maybe it will be enough for Costner to make a cameo, a lot of good picks there. AI can help with the aging thing.

It’s all one for the storybooks, but I’ll close with a quiet moment that summed it up for me. When I arrived at the entrance gate for Game 5, I said to the friendly parking attendant I see all the time, ”I’ll bet you’re sad it’s the last day of the season here at Dodger Stadium.”

”What do you mean it’s the last day?” he replied. “We have a parade next week. We’ll all be here for that.”

We had lost the game the night before and the series was tied at 2-2. There was no question in his mind there was going to be a parade. No question whatsoever.

Resilience to the end. Hope in the face of adversity. Optimism facing inescapable, ceaseless competitive resistance.

As Bart Giamatti wrote so eloquently about the game long ago, “It is designed to break your heart.”

Not this time.

Win or lose, this is the game we love.

________________________________________

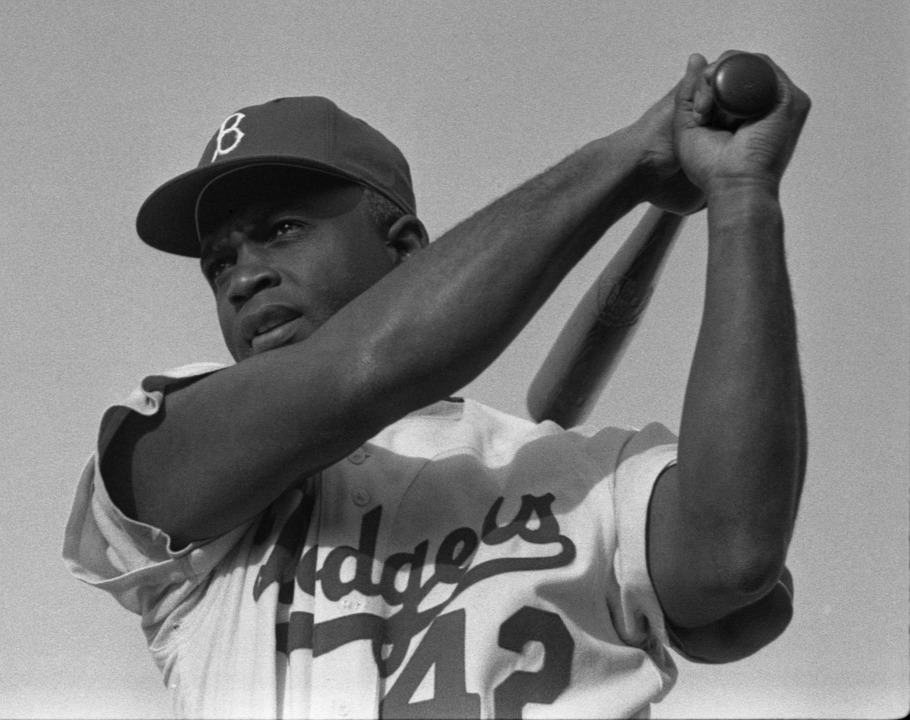

Photo: TORONTO, ONTARIO – NOVEMBER 2: World Series Game 7 between the Los Angeles Dodgers and Toronto Blue Jays at Rogers Centre on Sunday, November 2, 2025 in Toronto, Ontario. (Jon SooHoo/Los Angeles Dodgers)