Recently I shared with you my passion for philosophy. You probably know I also have a profound passion for business.

Recently I shared with you my passion for philosophy. You probably know I also have a profound passion for business.

And music, The Beatles, The Dodgers, wine, literature, children’s needs, social justice, and other stuff.

Back to philosophy and business: can they intersect?

This is where a lot of cynicism enters the picture.

Mark Zuckerberg says he is all about free speech and building global communities. He would have us believe a business—at least his business—should not be editing political expressions, even for accuracy. He asserts this is up to individuals to assess, or for the government to regulate if it can figure out a reasonable and fair way to impose guidance.

Should we believe Zuckerberg the visionary or Zuckerberg the voracious competitor? It doesn’t take a lot of analysis to know his goal is to keep selling ads, that any restrictions on free expression create a slippery slope for the addiction of his site contributors (i.e. all of us powering his pages with free content). It’s pretty clear he wants a level playing field around restrictions, meaning if the government regulates Facebook, he wants it to regulate all his competitors where he maintains a competitive advantage and is likely to win with ubiquitous rules.

Are free speech and “leave me alone to make money” compatible ideals, or the best possible excuse for self-interest?

Let’s try again.

Google’s stated mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” They are all about creating a definitive archive for global knowledge, about ensuring the best customer experience, and once upon a time about not being evil. That’s some philosophy!

Have you done a search on Google lately? Remember when organic search returns were clearly separated in columns from sponsored search returns? Yeah, that was before mobile made that largely impossible with much smaller screens. Today you practically have to be Sherlock Holmes to know what’s a paid ad on Google and what’s global knowledge. The keyword ads are everywhere. There’s a reason. They figured out how few bills the world’s information actually pays when displayed. They know which clicks are bankable in that trillion-dollar valuation.

One more for the road?

Apple wants us to believe it is at the heart of protecting our privacy, right to the edge of protecting the login codes of suspected dangerous criminals. Maybe that’s a big idea we have a hard time embracing because its scope means the tiny basket of bad eggs has to enjoy equal privacy if we want to protect the gigantic basket of good eggs.

Yet if privacy as a strategic mandate is a paramount position at Apple, how does the company abstract itself from all the apps that transmit our personal information to the data-mining servers of the world as fast as we type it in? Apple says it makes secure devices that are safe to use; that’s all they do and they do it brilliantly. If those devices open tunnels between those seeking data and those leaking data (again, all of us), that’s our tunnel to barricade or avoid, and it would be illogical to ask them to detour us otherwise.

Can a company have a point of view on elevated ideals, or are these polished notions just a bullhorn cry from the PR department?

I guess it all comes down to what we want to believe is a pure, important idea, and how far a company will go to spin a concept to its own advantage.

The issue is one of authenticity. Does a company truly embrace beliefs that are worth evangelizing, or are its statements around absolutes justifications of convenience?

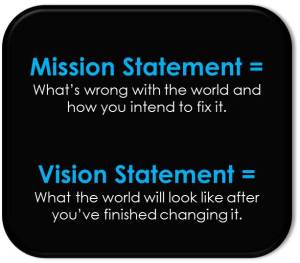

Proclamations are not philosophy. A mission statement is not philosophy. Company values are not philosophy. All of these are constructs meant to unify the purpose of a business, but the business entity’s constant struggle with ambiguity, competition, and the demands of ownership too often compromises ideas when financial interests are at risk. We can say we want to act in a certain way, but will we always?

I have to admit, I have been guilty over the years of trying to inject philosophy into business practice. I have not been terribly successful. The conflicts of interest abound, and the enormously hard work of maintaining consistency can be exhausting. I used to have my employees read a book called Freedom and Accountability at Work by Peter Kostenbaum and Peter Block. It is about existentialism in the workplace. All but one colleague told me they couldn’t get past the first chapter. At least they were honest about it.

How do we avoid hypocrisy and cynicism in a world where we want to be better? We are often told Millenials want us to rise to a higher standard, that cause-based marketing resonates strongly with their brand loyalty. I think it is possible to “do good while doing well,” but I don’t think we accomplish this if we pretend we’re something that we’re not.

Instead of declarations that render themselves hopelessly artificial, companies can humble themselves in restraining their platitudes around the possible. Instead of attempting to hide behind crumbling categorical imperatives, business might be better suited to achievable standards that are consistently authentic.

Tell me the truth all the time, and I may trust you. Don’t tell me why your definition of truth is defined in the unreadable footnotes at the bottom of the page.

Be aspirational, and I may join in the celebration of your mission and values. Don’t tell me that your company has discovered or defined a nobility that somehow makes you better than your competition.

Be well-meaning in the goods and services you provide, whether ensuring quality or seeking a healthier supply chain, and I may respect your brand. Don’t proselytize and expect me to believe you are pursuing a higher calling—profits be damned—when transparency betrays your more obvious motivations.

A business can be great, even legendary, without being philosophical. Let it be honest, consistent, and authentic—that’s plenty to tackle and enormously difficult on top of being outrageously good at something. The agenda of business is measurable, culminating in success.

Leave philosophy to the philosophers. Who would that be? That can be any of us—the storytellers around the campfire, the quiet voices in a coffee shop, the ardent dialogue in anyone’s home. The agenda of sharing, exchanging, and challenging ideas is immeasurable and ultimately boundless.

_______________

Photo: Pexels