Lately I’ve been struck by a surprising phenomenon finding its way into all kinds of discussions. That would be the expression of certainty.

It seems increasingly in many of the conversations I’m having that others have reached conclusions they feel no further need to revisit. It’s more than certainty. It’s absolute certainty.

Here are some varied examples:

Let me tell you what the Fed is going to do at its next meeting.

Let me tell you what the NASDAQ will do between now and Christmas.

Let me tell you how the conflict in the Middle East will end.

Let me tell you what Elon Musk is really after.

Let me tell you what’s ultimately behind climate change.

Let me tell you who is going to win the presidential election.

Let me tell you what’s going to happen to the nation after the election.

Note the lack of the words might, probably, likely, or even most likely. The statements above are followed by declarations of certainty. Needless to say, these utterances do not come from people who are experts in all areas of knowledge. Who can claim broad insight — approaching clairvoyance — across such a broad spectrum of complex topics? These statements are offered by ordinary folks whose opinions form much the way too many undisciplined declarations emerge in real time.

These days, I often find myself the least certain person in the room. I wonder, how can everyone be so sure about what they are proclaiming?

I work in a business where decision-making is data-driven. We have spirited arguments about work strategies all the time, and the boss doesn’t always win the debate. We argue with facts because there is shared value in our outcomes. Sometimes opinion prevails, but only when subjectivity is guided by objectivity.

We also require a lot of close listening before we get to conclusions. We know our choices have consequences on our company’s results, the actions of our customers, the well-being of our employees, and the financial impact on all our stakeholders. Data drives rigorous thinking. We take our choices seriously.

I realize company culture has little to do with random conversation or even the talking heads clamoring for attention on the media platforms that flood our lives. We are aware fake news creeps into all corners of communication. Somehow a justification for lying has woven its way into popular opinion, where the deliberate application of false information seems to some less of a vice in mainstream conflict if it is deemed a means to an end. Still, when I hear people parrot incoherent arguments expressed by others either for some concocted agenda or strictly entertainment value, it surprises me how willing we can be to compromise our credibility for nothing that would warrant it.

I wonder how so much claimed certainty continues to pierce our uncertain world. The internet fills our lives with noise. You’d think it would humble us to seek more truth before we convince ourselves we have found an answer. You’d think our personal character and integrity would matter more to us. We are endlessly willing to let a social media algorithm drive conflict in our discussions and stir our ire, rather than invest a bit of time validating our expressions before we pile onto the verbal brawl.

Do I expect this to change broadly anytime soon? Probably not. It’s too easy to speak without citing facts, to claim the right to say what we want, when we want, how we want, and believe this is without consequence because one voice self-corrected has little bearing on arena spectacle.

Yet that’s not true. One voice self-corrected is an example that leads to another and another. If those with authority won’t lead by example, imagine the influence of the broad population accepting the burden of that same leadership by caring enough to speak with a tad more precision.

I’m not suggesting anything outlandish. It’s a matter of individual commitment to modest self-reflection over boisterous hubris. Before you say something with absolute certainty, simply ask yourself: How sure are you?

_______________

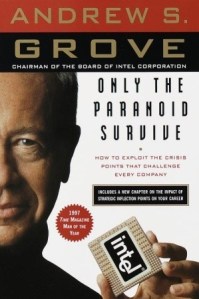

Photo: Pexels