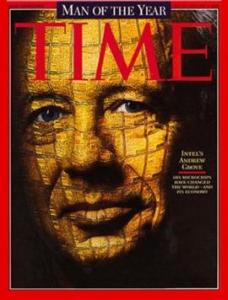

We lost a great business leader earlier this year. His name was Andrew S. Grove, known to many as Andy Grove.

We lost a great business leader earlier this year. His name was Andrew S. Grove, known to many as Andy Grove.

He survived Nazi-occupied Hungary as a child, then Soviet-controlled Hungary, immigrating to the United States at the age of 20 in 1956.

He received a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from U.C. Berkeley and became a star engineer at Fairchild Semiconductor.

He left the stability of Fairchild Semiconductor with Silicon Valley legends Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore when they co-founded Intel. Together they later entirely reinvented Intel from a manufacturer of memory chips to the dominant producer of microprocessors.

He was Intel’s CEO from 1987 to 1998, the famous “Intel Inside” years when personal computing exploded from the hobby to the consumer market.

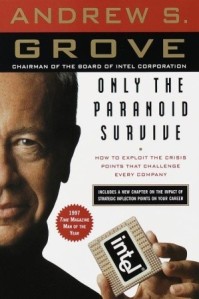

He wrote the legendary book Only the Paranoid Survive, published in 1996 and still a must-read for anyone who wants to understand innovation and the power of creative destruction.

For many years he co-taught a course in strategy with my dear friend Robert Burgelman at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

If you think everyday people always had the internet, email, streaming video, and smart phones, you have a loose grasp on current events, let alone history. Andy’s leadership at Intel took us from the 8086 to the Pentium chip, from monochrome to color displays, from floppy to CD disks, from no hard drive to software that could be installed. If you didn’t live through the transformation of the universe from analog to digital, from buying hardware and software at Computerland and Electronics Boutique to Best Buy and Costco, it’s hard to explain the magnitude of this growth cycle. Andy is one of those guys who really changed the world.

Okay, you get the point, about 0.001% of mortal beings have a resume close to his. You can read his full bio on Wikipedia. I want to share something more personal about him, the key takeaways from the few times I met him in person during roadmap briefings at Intel in the 1990s. Among the many lessons I learned from Andy Grove, here are five that continue to guide me daily:

- Creative Destruction Is Real – Whatever product you ship today is already obsolete, no matter how well it is selling. If you are not working on the replacement for it, someone else is. That is why you have to be paranoid. You will always be correct if you presume you are about to be outperformed in the marketplace of goods and service. Never get comfortable, never rest on your laurels, or you will be gone in a heartbeat, wiped off the map while you are collecting your awards for last year’s success. I learned from Andy that almost every startup that presumes it is built to last is almost certainly on a crash course with obsolescence, that the vast majority of even robust corporations today last about half as long as a human life. Companies don’t reinvent themselves, they are reinvented by courageous, visionary people.

- Beware the Strategic Inflection Point – By the time a market has fully morphed at scale, it’s way too late to react. You can’t see a strategic inflection point coming, you can only acknowledge it in hindsight while confessing your memoirs. Sorry, Monsieur Business Plan, the landscape changes in real time! Because you have learned to be paranoid, you are going to figure out one dreary morning that something you are doing in your company is hugely wrong. Some product you are readying for release is going to tank no matter how much you spend on marketing. Remember when Bill Gates discovered the internet? Remember when Mark Zuckerberg discovered mobile? Those were Intel-inspired moments. They turned their companies on a dime the same way Andy helped turn Intel on a dime when they realized the market for memory chips had commoditized and microprocessors were the way forward. I learned from Andy to always remain nimble, that sunk cost is always sunk cost, eat it and move on. Achieving competitive advantage before others see it coming is where your investments must be all the time.

- Science Is Inescapable – No matter what your market cap might be, you can’t fake math. Pithy slogans don’t make better computers, engineers do. For Moore’s Law to work (roughly twice the computing power will be available every 12 to 24 months for the same cost) staggering volumes of calculations have to take place on a tiny silicon chip without the transistors melting down. If you want to win at the engineering game, it takes the boldest and brightest team of advanced engineers you can assemble. They need the time to do the math, which is why Intel was already designing the 486 chip while shipping the 286. You can’t predict when the equations will be solved, you can only form a thesis and test your working models until they clear quality assurance. I learned from Andy that there are no sustainable shortcuts in quantifiable outcomes, the minimum viable product be damned! If you try to cheap your way through a poorly constructed algorithm, science will have its way with you and the result won’t be a proud moment.

- Constructive Confrontation Works – A lot of people who didn’t grow up in the Intel culture found it an impossible place to survive. Intel was a place where undisciplined, random conversation was never the norm. Almost anything anyone said could be challenged directly and aggressively by anyone in the hierarchy. Even when you were visiting Intel as a channel partner, anything you said could get shoved down your throat as instantly as you said it. Was this nice? It wasn’t meant to be nice. It was meant to improve products, driving ceaselessly toward unattainable perfection. That was how Intel maintained design and manufacturing leadership for a generation, by always challenging assumptions, never accepting compromise or forging an unholy consensus simply to move on. It isn’t the right culture for everyone, but at Intel, you bought into it or got your walking papers. I learned from Andy that in constructive confrontation, it’s always the idea that gets attacked and never the person. You might feel that you are being attacked, but you aren’t. Your ideas are being made better or mercifully eviscerated.

- Resilience Is a Mandate – Imagine a guy who made it from the Holocaust to the highest level of American thought leadership—all the obstacles, all the challenges, all the knock-downs, all the reinvention. To embrace the example of Andy Grove is to embrace the notion of resilience as the single greatest motivator available to anyone at any stage of emergence. You don’t give up, you don’t give in, you don’t quit. You always expect more from yourself. You learn from your mistakes, you study your failures, you learn from your adversaries. Want to survive? Want to triumph? Want to leave a legacy? There is no other way. I learned from Andy that you stay in the game, you look forward at opportunity, and you try again—only harder. Resilience isn’t a nice-to-have. Resilience is fuel for the soul.

Andy was a living example of realizing possibility through discipline. It is extremely rare to find an innovator with startup DNA who can personally evolve into the CEO of a multinational corporation. It is equally rare to find a top-notch engineer who embraces consumer marketing as a key strategic initiative. Andy championed the “Intel Inside” campaign as a branding mechanism that made an otherwise invisible component a necessity for personal computer manufactures to tout. When the consumer press seized upon an obscure failing in a sample of Intel microprocessors, Andy accepted the criticism as a byproduct of his brand promise. He insisted his team correct the deficiency with renewed quality assurance rather than defend the company’s position with arguments the consumer would never understand. He was book smart, business smart, and street smart all at the same time. He gave back way more than he ever took off the table in every way imaginable.

If you ever worked on one of my teams, I probably bought you a copy of Only the Paranoid Survive and quizzed you on it a week later. Andy’s words, thoughts, and ideas remain that important to me. He was an industry icon and a human being impossible for me to forget. I hope none of us ever forgets Andy. He remains a truly one-of-a-kind inspiration.

_____

This article originally appeared on The Good Men Project.

Photo: Time Inc.