As an investor, can you ever know for certain if that newfangled gizmo come to market is the real deal or a fad?

Let’s try it a different way—perhaps everything is a fad, until it’s proven otherwise.

Bread, most likely not a fad. But organic fair-market nine-grain soft crust, probably a fad.

Cars, probably not a fad. But eight-cylinder 130 mph muscle mobiles with no back seats could be a fad.

AM radio, possibly a fad, but one that has enjoyed a long shelf life—and now with news and sports retransmitted over the internet to mobile devices, probably a decent bit of runway left in the broadcast machine.

Farmville, Mafia Wars, and their brethren? You tell me.

Our attention spans are surely fickle, but just because something is a fad does not necessarily make it a bad investment. I am not certain internet keyword search will last forever, but the last decade and a half have proven pretty rewarding, at least for one company that currently commands better than 70% market share. Games? That’s where they come and go in a coughing breath—if you are going to bet at that crap table, come with a lot of chips and a jug of Pepto-Bismol.

The question of whether it makes sense to bet on a fad in a commercial, accelerated, low-loyalty, short-attention-span, vastly diverse, market-driven global economy seems moot. People have bet against railroads, phones, airlines, television, personal computers, and even guitar bands as fads—and that was before they had customers! Even after these “fads” had momentum, there were endless naysayers who said they were on their way out as fast as they’d found their way in. With that kind of outlook, eventually you have to be right, but you may be staring up at daisy roots when you finally win your bet.

There is tremendous Monday morning quarterbacking now about the dive in Web 2.0 companies, from Facebook to Zynga to Groupon to Pandora. Maybe they are all fads, but let’s separate the fad of stock market performance from the fad of consumer adoption as two separate issues. The shine may be off the stock, or the shine may be off the company’s products, but those are very different things. High-growth speculative stocks like these are most often valued on future earnings potential, not current performance, so if the stock is out of favor, that does not de facto mean the product or service has gone out of favor. Plenty of people are enjoying these consumables at the moment, though it is safe to say that they won’t all be in vogue for eternity. Styles change, tastes change, brand loyalties change. We know that to be Creative Destruction, an ever-present cycle, so when we criticize either an equity or a product as being a fad, let’s be careful to make the distinction, and even more careful not to level broad sweeping judgment that could lead to missed opportunity.

Can a company make money riding the wave of a fad? Seems to me that is more norm than anomaly. Can an investor make money owning the stock of a company that rides the wave of a fad without volatile exposure to market timing? Again this seems perfectly reasonable, depending on the window. Think Intel with micro-processing chips during the PC revolution, Electronic Arts with the rise of sports-based video games led by Madden NFL, and today’s True King of All Media, Apple. Equity markets in the long run reward smart risk and punish reckless risk, just as commercial markets reward desirable consumer offerings and reject cynical ones. There has to be risk for there to be reward or no one would invest, so the question is not whether something is a fad, but whether that fad represents some potential form of continuity recognized by visionary management as one in a string of ventures that together comprise opportunity.

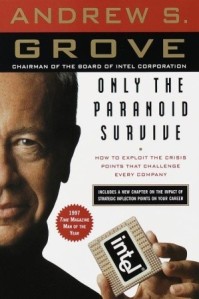

Intel’s legendary former CEO Andy Grove clearly taught us, “Only the Paranoid Survive.” He knew at any strategic inflection point the difference between a fad and a trend was largely the expanse of the product life cycle. More importantly, he worried about management culture as the path to product culture, where innovation means never-ending creativity, not tossing the dice and getting lucky on a good roll. I don’t worry whether a company is profiting from a fad, I expect companies to be opportunistic. I worry whether the company is a one-trick pony, whether it has created a learning culture where success and failure are both studied. A company that has learned to learn, that can read data and understand how fads are perpetuated as trends that constitute periodically sustained disruptions—that is a company that can extract true shareholder value from a fad, foremost by surprising and delighting customers repeatedly with that which they never expected was possible.

Intel’s legendary former CEO Andy Grove clearly taught us, “Only the Paranoid Survive.” He knew at any strategic inflection point the difference between a fad and a trend was largely the expanse of the product life cycle. More importantly, he worried about management culture as the path to product culture, where innovation means never-ending creativity, not tossing the dice and getting lucky on a good roll. I don’t worry whether a company is profiting from a fad, I expect companies to be opportunistic. I worry whether the company is a one-trick pony, whether it has created a learning culture where success and failure are both studied. A company that has learned to learn, that can read data and understand how fads are perpetuated as trends that constitute periodically sustained disruptions—that is a company that can extract true shareholder value from a fad, foremost by surprising and delighting customers repeatedly with that which they never expected was possible.

I have a lot of criticism about this year’s poor performing new entries in the NASDAQ, but that criticism has nothing to do with whether those companies were beneficiaries of identified fads now assessed by pundits to be in decline. My own career has been the beneficiary of any number of fads that came and went—computer games that sold millions and now barely qualify as second round questions on Jeopardy, once immensely cool websites that scored millions of visits that no longer can be found, virtual communities that ranked with the best in loyalty and now would be lucky to make the card draw on Trivial Pursuit. Does that mean they weren’t good businesses that added significant value to their owners? To the contrary, in their useful lives they added exceptional shareholder value in earnings and lifetime contribution. We worked the brand promises as long as we could, but when their time was done, we moved on.

That’s why a sweeping statement like “don’t invest in fads” makes little sense, because if virtually everything is a fad with varying sustainability, there is no choice but to invest in fads. What I worry about is management vision, how the brand stewards of a company are migrating from one fad to the next, how maneuvering through Creative Destruction is an art and science unto itself. Edison did it over a very long period of time. So did Steve Jobs. The folks who run television networks have to do it, because no show lasts forever and formats are cyclical; yesterday’s Variety Shows are today’s Reality Shows, half-hour comedy goes in and out of style, so does one-hour drama. Walt Disney famously bet the ranch on 2D feature animation, clearly a fad, although one he created and that lasted more than 50 years—but that wasn’t the only trick he had in the magic shop, not even close. To invest wisely in the likelihood that originators can capitalize on a string of fads through creativity and experimentation is very different from investing in one hot rocket that goes straight up with full knowledge that gravity will send it back down with equal and opposite thrust.

As the contemplative George Harrison reminds us, All Things Must Pass. That doesn’t mean windows of opportunity aren’t always in abundance. Watch the fad-makers, not the fads themselves, and the game changes significantly. While even the best fad-makers can’t call winners forever, those longer windows leave plenty of room for upside, especially when you bet the full spectrum of an index rather than trying to call the hits in isolation. If you bet on a one-trick pony and lose your bait, that was most likely your mistake, not that you bet on a fad.