Facebook moved into a new office complex earlier this year, which Mark Zuckerberg has described as “the largest open floor plan in the world.” With over 400,000 square feet, it is reported not to offer a single private office. There are conference rooms, shared spaces, and all kinds of creative gathering areas meant to protect the startup environment that is core to the company’s zeitgeist as it evolves into a corporate behemoth. It’s a wild, energetic, real-time experiment in organizational development that is already being praised and criticized from inside and outside the company. Whatever your assessment might be, it’s a test of human behavior worth watching.

Facebook moved into a new office complex earlier this year, which Mark Zuckerberg has described as “the largest open floor plan in the world.” With over 400,000 square feet, it is reported not to offer a single private office. There are conference rooms, shared spaces, and all kinds of creative gathering areas meant to protect the startup environment that is core to the company’s zeitgeist as it evolves into a corporate behemoth. It’s a wild, energetic, real-time experiment in organizational development that is already being praised and criticized from inside and outside the company. Whatever your assessment might be, it’s a test of human behavior worth watching.

For a moment, I’d like to think of the Facebook campus not as a model of space planning, but as a model of team planning. Long before the debate raged on whether private offices had run their course of usefulness—and just how truly dreadful the industrial cubicle could be—company leaders were debating the “optimal” way to arrange organizational charts in the Information Age. If you’ve spent any time with me in product development, you know I like to quote the sometimes overused phrase, “People in companies get stuff done in spite of org charts, not because of them.” It’s a bias I maintain for all kinds of reasons, not the least of which is seeing it in action almost every day. Another bias I hold applies to the “optimal” way to build these org charts. I’ll confess to that in a moment, but the title of this article has likely already given away my leaning.

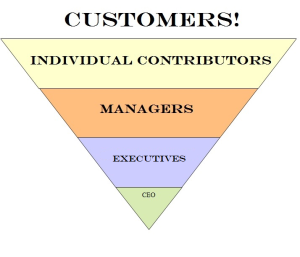

Let’s start with the basics. The rise of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century, emerging from prior Agrarian Societies, led to thousands of individuals working for single companies, for the most part creating efficiencies in the manufacturing model. Most of us are familiar with the innovation of Henry Ford as something of the father of mass production with his 20th Century Assembly Line. The premise of the organizational charts for these early corporate conglomerates surmised that a few knowledge workers and a Big Boss would send instructions down the pyramid to a wide base of workers who hopefully wouldn’t ask too many questions. Executives were at the top, middle managers squeezed in the sandwich, and individuals contributors down below busy doing their hands-on functions repeatedly. If the model sounds blunt and easy to follow, there is a reason for that—it dates back to the earliest days of broad warfare, mostly perfected by the Romans. You have an Emperor, you have Generals, you have Captains, and you have Soldiers. It worked for thousands of years in capturing terrain, albeit at the cost of mostly Soldiers, and it worked for hundreds of years in mass producing products, too often without much consideration of job satisfaction.

As education and information became more available in later decades, and asking questions became the norm, the inflexible org chart became a lot more difficult to maintain. As workers collaborated more and followed instructions less, human resources departments (formerly known as personnel offices) looked to break out of the traditional top-down structures and unleash creativity. Standard org charts evolved along the lines of two basic models: Functional Departments and Cross-Functional Teams.

Functional Departments place similarly skilled workers into groups led by senior individuals with advanced experienced in a discipline. This creates a Legal department, an Art department, an Engineering department, a Finance department, a Sales and Marketing department, and the like. Over the course of your career you might aspire to become the VP of Finance or the VP of Marketing, and these VPs, now sometimes called C-Level executives (Chief Financial Officer, Chief Marketing Officer) point the functional expertise of their teams into a Chief Executive Officer. Your company may organize itself this way. It is a very common and familiar way to organize. It’s also still very close to the old military hierarchy.

Cross-Functional Teams break the model of Artist reporting to Art Director and Engineer reporting to Engineering Director. They place multi-disciplinary groups under a generalist manager who is often more “cat herder” than boss. In this model, a smaller group of people with engineering, finance, marketing, design, and manufacturing expertise might all report to someone called a Project Lead, Product Manager, or General Manager, who is in essence a mini-CEO. Unlike Functional Departments, Cross-Functional Teams are likely to be less “permanent” in structure. The team might be ad hoc, assigned to an initiative, ready to be broken up and redeployed following a product release. Functional experts on the team might have a dual reporting relationship to the team leader and a senior expert in their area of expertise offering professional mentorship, so that a team leader who doesn’t know the law doesn’t have to render legal oversight (always a good idea). Over time Cross-Functional teams can evolve into more permanent Business Units with profit and loss responsibility for a specific line of products and extensions. If you have ever been in a company comprised of Battling Business Units , you know it can be even less fun than being buried on a Functional Team.

It is at the intersection of these two models that we all learn the necessity of Matrix Management, which unfortunately in the Information Age is the only real way we have to collaborate in an ongoing manner. Sometimes we need a Functional Department to help us advance in our area of expertise, and sometimes we need a Cross-Functional team to get stuff done with people who are good at different things. Most companies go back and forth between Functional Departments and Cross-Functional Teams, and just when you think your company has settled into a comfortable structure, along comes the inevitable memo announcing the company re-org. Companies re-org over and over in search of optimizing their growth models, but the truth is, neither approach is perfect, and whichever one your company is currently utilizing, be prepared to have it change. Re-orgs are certain because change is certain. The opposite would be sameness, and as much as you might think you want that, running in place is the surest way possible to go out of business.

Oh, about that bias of mine—I believe anything in a company that leads to entrenched fiefdoms stalls creativity. Functional Departments are usually fiefdoms. Business Units are usually fiefdoms. Again, this is why Matrix Management is a reality, particularly in managing empowered, innovative individuals who join together in a mission that is unlikely to last a lifetime, but has a real chance to change the world now. If we take that back to the visual metaphor of the open floor plan, I tend to see greater strength in the output and engagement of Cross-Functional Teams than I do Functional Departments. That doesn’t mean I am against having an exemplary CFO, CTO, or CIO setting the bar for excellence in a discipline. It just means that whatever the org chart says at the moment, I don’t want any walls between artists talking to engineers, lawyers talked to sales people, accountants talking to marketers, or anyone so distant from customers that they forget who pays everyone’s salary.

You see, at the root of all this, there only is one Emperor, one General, one CEO, one Boss who matters most. That is the voice of the Customer, whom we almost never place on the org chart. Start by putting the Customer at the top of the hierarchy, and you’ll soon understand why who reports to whom doesn’t really matter when it’s time to tally the scorecard. That’s why the walls gotta go, figuratively or literally. Go out on the floor and try to bump into a few people. You may be surprised how much you learn and how good it feels.

_____

This article originally appeared on Inc.