Last month I wrote briefly about the fallacy of the upper hand. The responses I received from people navigating similar bouts of forced will remind me how not normal our lives remain. Over the past year and a half, many employees have learned to work remotely, and to some the routine of working from home is now its own form of normalcy. At the same time, we are increasingly returning to the workplace and trying to adjust to the structure of sharing a space with colleagues and strangers for a third of each day.

To assume everyone can walk back into the workplace and public spaces without some enhanced focus on conduct seems to me naïve. Human beings are certainly adaptable, but I worry that we might be presuming a level of adaptability that confuses the comfort zone of individuals with the smooth functioning of collective interests. You’ve no doubt heard about the outbreaks of passenger rage on commercial flights. They are not as isolated as we might want to believe.

Covid-19 has taken away a lot of daily practice from our interactions. It’s not just that it is easy to forget how different it is to interact in person than it is to communicate through electronic platforms. Talking into screens is not a fully rendered substitute for being together. We have developed habits in our physical solitude that have taught us to be effective in doing what is expected of us, but some of those habits may not make the most of opportunities to emerge with a broader purpose. We may find it easier to behave in certain ways when we are alone than when we are together, and bridging those geographies may not be as simple as flexible switching between environments in what many now label as hybrid work.

There is more to the next generation workplace than where we do what we do. There is a mindset I think we need to share—a set of shared values—that seems to me more traditional than circumstantial. If we want to adapt to new paradigms for interacting, perhaps the rules governing those interactions are agnostic to place. It seems critical with the perpetual noise around us that as we adjust to the new back-to-work standards we insist on a standard of decency in our endeavors.

In recommitting to an extraordinary standard of civility, here are four simple pillars I would expect of myself and others.

Tell the Truth

When I say tell the truth, I mean all the time. It’s easy to tell the truth when it is what others want to hear and it avoids controversy. It is much harder to tell the truth when we have made a mistake, when data is being manipulated by someone in authority, or when the cost of that truth is one’s own popularity. The problem with honesty is that it can’t be a tool of convenience. We must tell the truth not because there is penalty if we don’t, but because we cannot universally insist on it from others if we don’t stand by the promise that it is inarguable. Understand what is empirical and fully embrace integrity. Silence when the truth is known is not a noble dodge, it is another form of mistruth.

Your Name Belongs to You

Unless one’s life is at risk for civil rights abuses, most of what people author anonymously is cowardly. We can argue the difference between old media and new media is the presence of an editor creating an artificial funnel on access to audience, but one of those old school norms was the expectation in authorship of identity. We should write with a by-line, with our name associated with our thoughts, and with our style of verbal and written communication enhanced by our ownership of that expression. You have only one good name. Protect it through accuracy, clarity, absence of pointless invective, and even if eloquence is beyond reach, at least frame the deliberate use of language in a context that is purposeful.

Manners Matter

We can stand on our authority, or we can strive to get people on our side. It has never been clearer to me that style is content, that the outcome we are trying to achieve is inextricably linked to the form of our argument. Approach those around you with respect and there is a much higher chance they might be interested in the thought behind the point you are making rather than just the interpretation of their role in the outcome. Avoid the opportunity to build consensus at your own peril, but even when you must deliver the top-down tiebreaker, do it with finesse, restricting the hammer to the impossible sell. The Golden Rule survives the centuries because some ideals do make sense even when we fail ceaselessly to take them seriously. Hear the words you are saying. Would they get you encouraged, inspired, and onboard?

Think Long

Survivors know that careers can last or not. The yes you got today—the yes that was so important you worked tirelessly for months to hear—is as fleeting as any other decision in the moment. Short-term action without a long-term framework is a high-risk gamble. Telling a half-truth might get you to the end of the week. Cleverly masking your name from an unpopular report might get you through the review cycle. Effectively bullying a coworker might swing a lost debate to your advantage. All of those will cost you. Steve Jobs used to talk about brand deposits and brand withdrawals. You need both in balance to build a lasting brand—to establish and reinforce a credible promise. You can’t make deposits and withdrawals at random and go “up and to the right” repeatedly without a plan. The winning strategy when others are winging it is to think long.

Welcome to the new world. Sounds a lot like the old world, only with less commuting. Count me in.

_______________

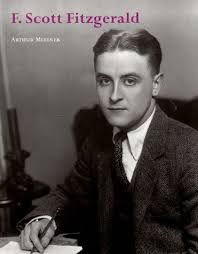

Photo: Pixabay